Family Storytelling

- Jun 16, 2016

- In Features

We all know how beneficial reading to children is. Studies also tell us that family storytelling – reminiscences about our own childhood, family stories going back through the generations – is linked to a range of benefits, beyond literacy and communication skills. Family storytelling can help children to develop their social and emotional skills; provides a framework for understanding the self and emotion; contributes to resilience, strong self-esteem and a robust identity.

Marshall Duke and Robyn Fivush have explored the reasons behind the fact that people who know more about their families seem to be more resilient. The psychologists developed the ‘Do you know?’ scale, a tool that asks children 20 questions, to test their knowledge about themselves and their families. This tool, together with observation of family dinner conversations and other psychological testing, revealed that:

The more children knew about their family’s history, the stronger their sense of control over their lives, the higher their self-esteem and the more successfully they believed their families functioned. The “Do You Know?” scale turned out to be the best single predictor of children’s emotional health and happiness.

Obviously, the relationships between family storytelling, knowledge of one’s family history, and emotional well-being are complex. Knowing ‘the facts’ about one’s genealogy isn’t going to lead automatically to a coherent sense of self, a robust identity and an overall sense of stability and well-being. And what happens to one’s sense of self when the facts of your personal and family stories are not easily established? This issue is highly relevant to the lives of people whose childhood involved experiences of institutional ‘care’.

It is well established that a childhood in ‘care’ nearly always involved significant disruption and trauma (sometimes intergenerational) within families, with the result that the most basic knowledge about a person and a family’s past and identity was lost. Telling the family history of Care Leavers – ruptured by traumatic and chaotic circumstances, not to mention secrets and lies – requires particular genealogical expertise.

On the ABC website, there’s a fascinating story by Sally Sara about her family, called The Boy Who Shot My Nanna. Her grandmother’s life was profoundly affected by a 14 year old boy called Ronald Albert Sharpe (the title of the story gives you an idea of how). Sara’s piece contains two very different family stories – the story of her own family is largely pieced together from conversations, photos and memories.

My nanna’s neck was wrinkly, as nannas’ necks often are. But I remember quite distinctly the remnants of a scar.

“You see that? That’s where he shot me.”

The scar was barely the size of a 5 cent piece and the wrinkles made it harder to find, year by year. But nanna could point to the exact spot on her neck without even looking.

I can’t remember being told the story for the first time. It was just something I knew. I thought everyone’s nanna had a scar like that. My brothers and I didn’t pay much attention. Our curiosity ran on two different speeds — politely bored when we were told the stories we were allowed to know and insanely fascinated by those we were not.

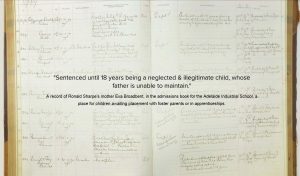

The piece also tells the family story of Ron Sharpe. The boy who shot her nanna was a ward of state, on work placement at the family farm. The telling of Ron’s story is reliant on different sources – primarily archival records, detailing several generations of his family and their experiences of institutions, including the Parkside Lunatic Asylum and the Edwardstown Industrial School.

The ‘Routes to the Past’ project, funded by a grant from the Melbourne Social Equity Institute, is exploring some of these issues. Routes to the Past brings together an interdisciplinary project team to look at the ways that Care Leavers use family history and institutional records to tell their stories. The project is investigating whether theoretical approaches like narrative practice and therapeutic life story work could usefully be applied in work to support Care Leavers to understand their past and to tell their stories. We are holding our first project workshop in July 2016 and will be publishing a discussion paper in months to come.