Encounters with the Immigrants' Home - part 1

- Aug 24, 2017

- In Features

For National Family History Month, we are publishing a blog post (in two parts) by Helen Morgan, Senior Research Fellow at the eScholarship Research Centre.

It saddened my father that he knew nothing about his own father’s family.

My paternal grandfather, Bill Morgan, was one of 12 children born between 1884 and 1912 to Gabriel and Ellen Morgan. I never knew him. He passed away when my father was 13. Dad never knew his grandfather Gabriel either, who passed away a year after Dad was born. There were fond memories of walking Melbourne’s outer circle railway to East Malvern, hand in hand with his father to visit his grandmother Ellen (‘a lovely lady’), but after Bill’s death that was it. No more contact with the paternal family. I still don’t know why. An artefact perhaps of being part of a very large family.

I began with my great grandfather Gabriel. After starting sensibly by searching births, deaths and marriages in Victoria, I moved on to the digitised Australian newspapers in the National Library of Australia’s Trove.

Not expecting much, though hoping, I was floored not only to find my great grandfather but to feel so drawn to him. For there he was in 1873, a 12 year old, found wandering the streets of Melbourne by the police and subsequently brought before the City Court as a neglected child.

Gabriel had abandoned his employment in the country and found his way back to Melbourne. He had been living on the streets of the city for six weeks. He had looked for his family at the address where he’d last known them to be, in Richmond, and found them gone. The court placed him in the Immigrants’ Home for seven days while they investigated his story.

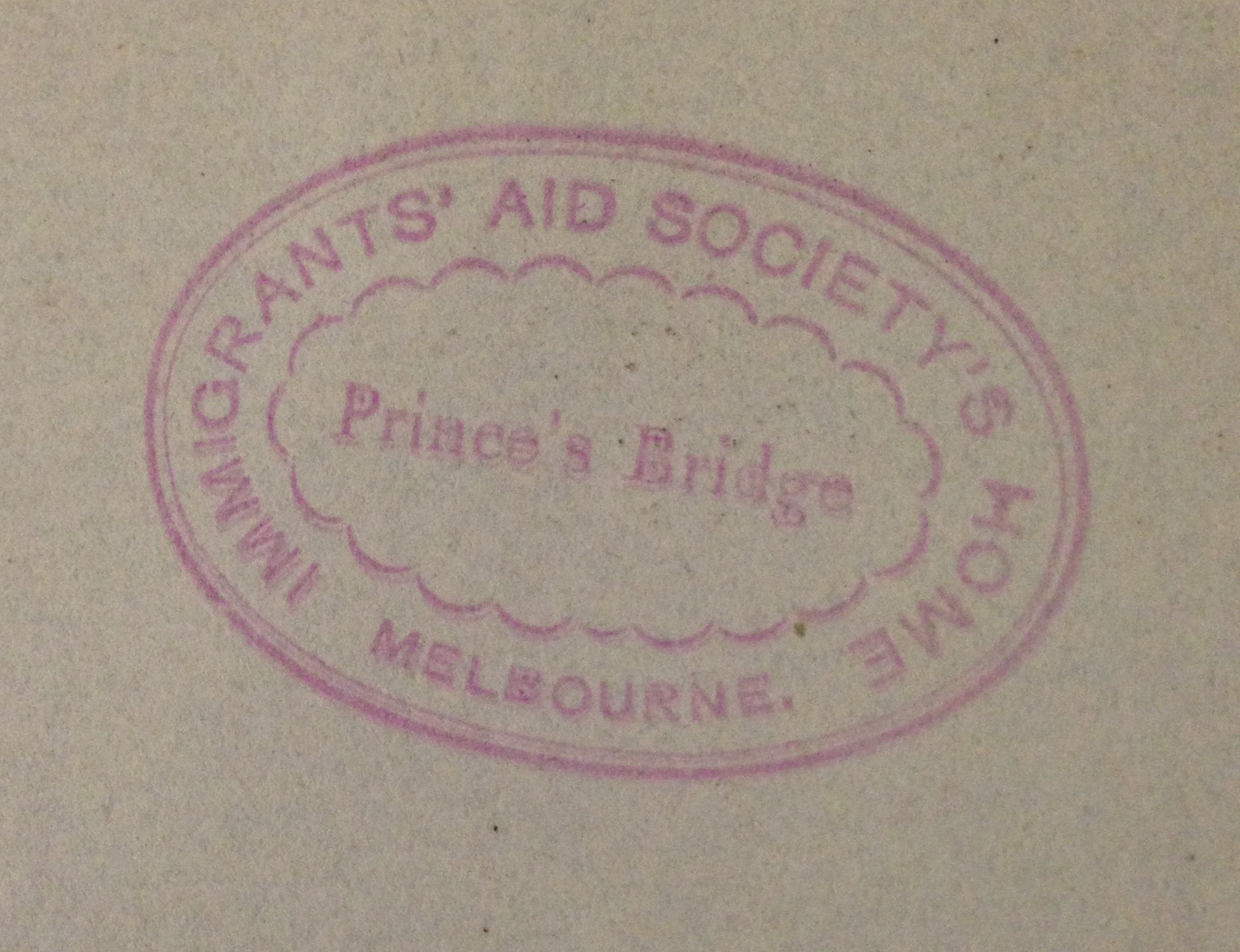

Googling led to the Find & Connect web resource, which has a great entry on the Immigrants’ Home, referencing a number of contemporary and secondary sources about the Immigrants’ Aid Society, the institution’s official name. The ‘Home’ referred to a jumble of buildings straddling St Kilda Road, south of Princes Bridge and the Yarra. It was established in 1853 by the Immigrants’ Aid Society to do as the name suggested, quickly outgrowing its remit. The Age noted of it in 1874:

it is found that as early as 1856 its operations were extended by request of the magistracy to cases of distress, the relief of which was not contemplated by other charities; and we find further that in 1857 another phase of poverty presented by numbers of deserted destitute children being found by the police was dealt with by such being admitted into the Home at the cost of the State, a step taken also by request of the Government (11 August 1874, p.4).

The newspaper reports that recorded Gabriel’s appearance before the court indicate that he was admitted to the Immigrants’ Home on Tuesday 14 October 1873, a period when the Home was deemed ‘disgracefully crowded’. (The Argus, 2 October 1873, p.6) There were more than 400 people in the Home at this time – 282 men, 84 women, and 83 children. (The Argus, 18 October 1873, p.5) There only seven days, it was likely that Gabriel was put to work ‘in exchange for the relief given’. (The Age, 11 February 1873, p.2)

I don’t know what happened next, but Gabriel was one of the lucky ones. He was clearly engaging and bright, and ‘won the sympathy of everyone in the court’. Perhaps this and his gender worked in his favour, because I found no record for him in the Industrial School registers (the likely fate for a ‘neglected’ child at this time), and no more records until sighting him ten years later, in a newspaper notice of his marriage to Ellen. I suspect that someone at the court that day in 1873 stepped up to help him, and offered him work. Perhaps he was even reunited with his family.

The Immigrants’ Aid Society continued to evolve its focus through to the present day. It is now a specialised aged care facility, run by the Royal Melbourne Hospital at Royal Park. Providentially, there are some records relating to the Immigrants’ Home held by the Hospital Archive. I’ve checked the monthly minute books for October-November 1873 in the hope of finding out more about Gabriel and didn’t; however, the minutes reveal that the Immigrants’ Home found other boys apprenticeships during this period (four apprenticed to shoemakers and one to a bookseller in 1872).

Picturing Gabriel on the streets of Melbourne, ‘constrained to seek shelter in a gas pipe, or camp out in the Yarra scrub’, along with all I have subsequently learnt through registers, records and newspapers, has changed my perspective on both the city and my family. Sadly, almost nothing of these discoveries I shared with my father, who passed away within months of me starting this research for him.

Notes/Sources:

The Royal Melbourne Hospital Archives hold records of the Immigrants’ Aid Society (Accession 1346) including admissions (from 1885), roll books (from 1880), an index to inmates (1884-85, 1889), statistical register of inmates (1878-1884), and minutes. Salient information from the minutes of the monthly committee meetings, including names and details of those who died in the Home, was regularly reported in the Melbourne newspapers in the nineteenth century.

Key newspaper articles mentioned in the text relating to Gabriel include:

- 1873 ‘NEWS OF THE DAY’, The Age (Melbourne, Vic. 1854 – 1954), 15 October, p.2, viewed 25 July 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article202520627

- 1873 ‘WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 15, 1873’, The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. 1848 – 1957), 15 October, p.4, viewed 25 July 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article5873674

- 1873 ‘GENERAL NEWS’, Weekly Times (Melbourne, Vic. 1869 – 1954), 18 October, p.11, viewed 25 July 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article223791839

Author: Helen Morgan

Helen Morgan is an archivist and senior research fellow at the University of Melbourne eScholarship Research Centre. She is co-editor of the Australian Women’s Register.

Rachel

September 2, 2017 2:42 pmGreat piece Helen and also loved Frank’s comment – both are illuminating and moving. Sounds like many would have been better off left in the streets, but I imagine they were ‘unsightly’ and discomforting to passers by.

Helen Morgan

September 4, 2017 12:06 pmThanks Rachel. I think you’re right.

Frank Golding

August 25, 2017 12:26 pmI enjoyed reading the story of your great grandfather Helen, and I look forward to Part 2. I think Gabriel was very lucky to have spent only seven days in the Immigrants Home. As you point out, it was “disgracefully overcrowded” in 1873. But there was nothing new there. In 1865, my own great grandfather, Edward Sinnett (then aged 11), was one of the hundreds of children, “street urchins and youthful Bedouins”, rounded up and sent to the Immigrants Home under the new Neglected and Criminal Children’s Act 1864. The Home was in crisis—a disease-ridden, lice-infested and dangerously over-crowded hellhole. An outbreak of ophthalmia left many children completely blind. Some 117 children died in that hell-hole that year (Report of the Inspector Industrial Schools, 1867: p. 3).

In 1879, looking back, an official reported that the period after the Neglected and Criminal Children’s Act was one of “continuous and wearying efforts to obtain accommodation for the children. Quarantine station, immigrants’ shelter sheds, military barracks, penal hulk, gaol, war ship, and powder magazine being made successively to do duty in sheltering the children; the one characteristic being common to the whole, viz., utter unsuitability” (Annual Report of the Department of Industrial and Reformatory Schools for 1879, p.3).

Lucky Gabriel!

Helen Morgan

September 4, 2017 12:18 pmThanks Frank. The figures are beyond comprehension, aren’t they.

Through accessing Gabriel’s will I learnt that he wanted to leave money to the Minton Boy’s Home, which Find & Connect tells me had its origins in the Latrobe St Ragged School and Mission. I have speculated this may be because around this time of homelessness and unemployment in the 1870s Gabriel received help from them. I think he may have realised how lucky he was too. (The will, however, was ruled invalid, so his wishes perhaps to pay the luck back were never realised.)