Own Your Story, Own Your Mob, Mob Owns You – Re-authoring the colonial archive

- Jan 29, 2021

- In Features

This was one of our most popular blog posts last year. So much happened in 2020 that it was easy to miss great stories in amongst the raging fires, the floods, and of course the COVID-19 pandemic, and we want to make sure you have the chance to catch up with them. We won’t reblog all our posts, but keep an eye on our twitter account where we’ll highlight some of the best. That way, you won’t miss a thing.

GUEST POST: Kath Apma Travis Penangke is “a proud Imarnte woman of the Arrernte People of Central Australia, Sovereign woman, stolen generation survivor and First Nations Historian”. She was granted the Lisa Bellear Indigenous Research Scholarship to undertake her PhD studies at Victoria University.

Family history is essential – it helps us to understand ourselves, it keeps memories alive, and most importantly it allows each generation to have an idea of who they are and where they come from. Throughout history, family tradition, culture and memories have been passed down through the art of storytelling. These stories help new generations connect to their history to know their story.

My research comes from a personal place, it’s an extension of the history within my family, 54 years of searching for my identity and trying to belong. It began as I searched to understand my own story. A stolen generation survivor born in 1965, I was one of five women in my family across three generations who had been forcibly removed from each other and family spanning from 1920 until 1969.

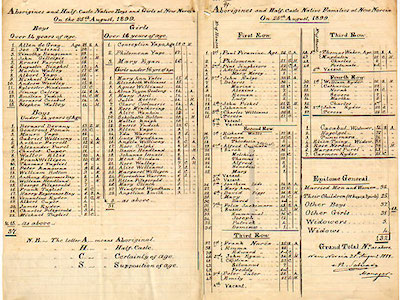

The colonial archive continues to have a disempowering impact on our people whose lives have been extensively documented and controlled for the purposes of surveillance and dispossession. The archival legacy of discriminatory treatment continues, resulting in First Peoples’ stories still locked in police files, child welfare reports and privately owned records and kept hidden in repositories, meaning we are not always able to locate our story or own our identity. One of the challenges for me was gaining access to the United Aborigines Mission (UAM) records, where many First Nations people stories including my Matye’s (mother) are held and these records continue to not be available to those that were in various institutions controlled by the UAM.

My research took me to various places and like most other First Nations people, my experience of accessing the archives is one of receiving a chilling and intimate family snapshot into the lives of myself and my family under extraordinary surveillance. Unravelling the settler fantasy that had attempted to silence our voices, not because we were not in the archives but because we were, was addictive and satisfying.

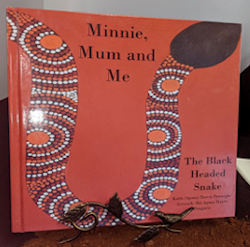

So throughout my five years of researching my family story – I was encouraged to enrol in University. With the support of the family Matriarch, my Matye I graduated with Honours in 2019 and self-published my family her-storical biography titled Minnie, Mum and Me: The Black Headed Snake as part of my Bachelor of Arts Honours Degree. Untwisting the colonial voice, changing the story, empowered the family to know the story, understand the story, re-tell the story and re-patriate the story back to country.

Minnie, Mum and Me: The Black Headed Snake

To celebrate Family History Month, the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) hosted for the first time, several free online family history sessions and I was privileged to collaborate with them as guest speaker. I shared tips and tricks to my archival exploration and provided insight on the re-authoring practice that has helped my family and me reconnect to our Country and understand our identity.

We as First Nations people are agents capable and interested in research, and we have expert knowledge about ourselves so the power of authoring our family narratives, how we re-claim our stories – not ones written about us, but stories written by us as a method of re-writing history from a First Nations perspective can play an integral role in understanding identity.